Both Personal Safety and Process Safety have the potential to significantly impact organisations (Ismail Y.Mataqi, 2013).

While both Personal Safety vs Process Safety are crucial, there are several myths surrounding these concepts that need to be debunked.

What is Process Safety?

A disciplined framework for managing the integrity of hazardous operating systems and processes by applying good design principles, engineering, and operating and maintenance practices.

It deals with the prevention and control of events with the potential to release hazardous materials or energy. Such releases can result in toxic effects, fire or explosion, and could ultimately result in serious injuries, property damage, lost production and environmental impact.1

Often there is a misperception, that process safety is only related to mining, oil & gas industries. Many workplaces have the potential to require the management of process safety.

Let’s challenge the status quo and shed light on these misconceptions.

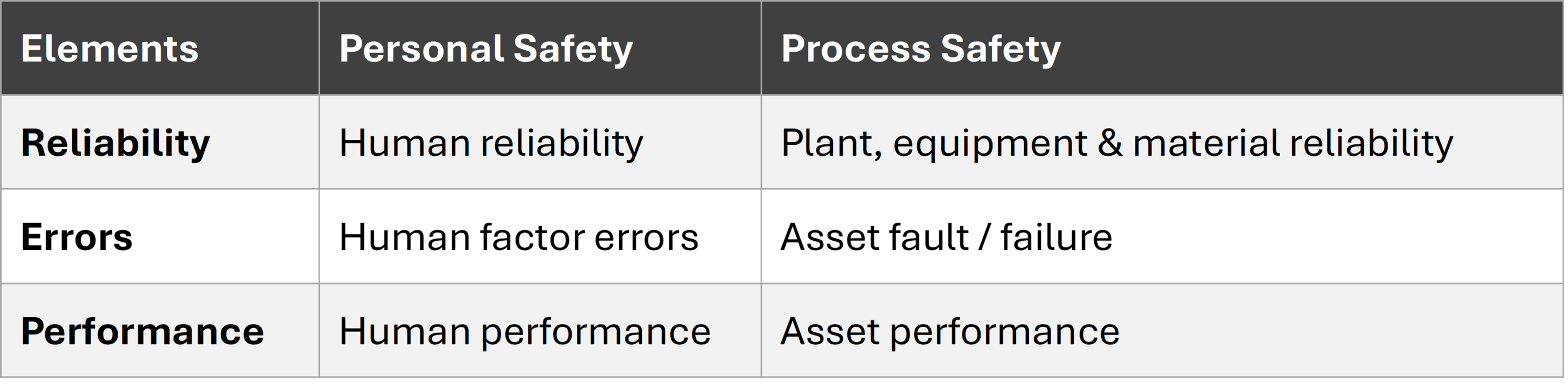

Table 1: Personal vs Process Safety

Myth #1: Process safety can be distinguished by consequence.

Contrary to popular belief, the severity of an incident alone is not a distinguishing feature of process safety. While process safety generally involves higher potential consequences 2, the severity of potential incident alone is not a distinguishing feature. Personal safety incidents can also result in catastrophic consequences such as multiple fatalities.

For example, safety oversights in a confined space could lead to a catastrophic event with multiple fatalities due to asphyxiation or toxic exposure. Similarly, a failure fuel pipeline during a critical operation could result in several fatalities.

Both types of safety concerns are integral to the overall health and safety management and require diligent attention to prevent serious consequences. While process safety incidents may have a broader impact, personal safety incidents can also have severe and tragic outcomes, underscoring the importance of comprehensive safety management that address both areas effectively.

Myth #2: Critical Risks / Material Unwanted Events (MUE) relate solely to potential fatalities.

Material Unwanted Events (MUEs) often referred to as Critical Risks, do not solely relate to fatalities. They also encompass the potential for major or catastrophic events 3. The threshold of MUE’s often relates to a business’s risk appetite and risk tolerances, i.e. What is material to your organization.

For example, in high-risk industries like mining, oil and gas, and construction often have very little tolerance of corrosion to critical assets. A catastrophic event from corroded fuel pipes and explosion may not necessarily result in a fatality, but is still often considered material.

In practice, identifying high energy sources / hazards, material risks or MUEs involves a systematic approach to risk management. Balancing Personal Safety vs Process Safety (Table 1), involves a risks-based approach to effectively manage critical assets, activities, processes and workplace environments, e.g.

- Critical Assets: What are the critical assets? How do design, construction, operations, maintenance and inspection teams collaborate to prioritise critical assets to ensure they are fit for purpose?

- Critical Activity: What are the critical activities associated with assets and other work activity?

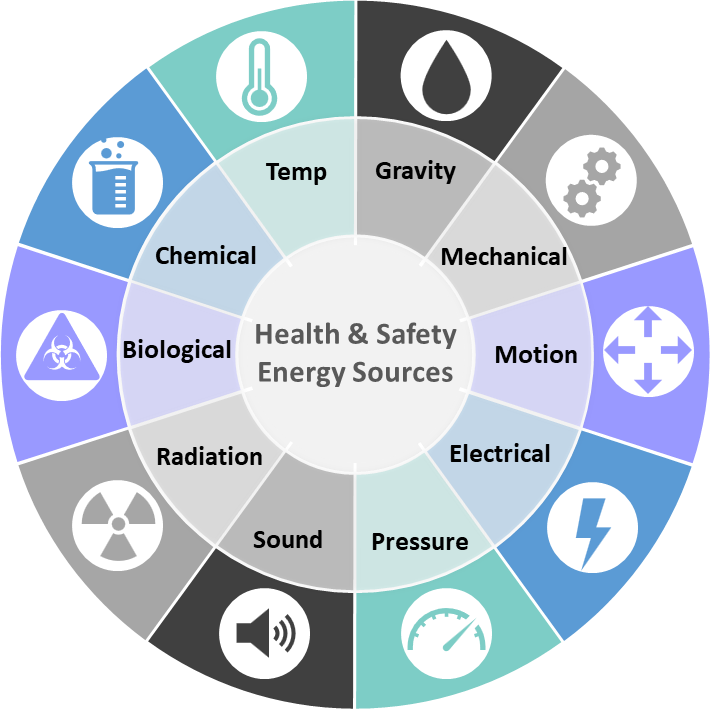

Figure 2: High Energy Sources Model (Safety)

For more information on identifying MUE, refer to our Critical Control Management blog – The Unintended Consequence of Gettng in Wrong: 5-Part Webinar Series.

Myth #3: Personal safety only relates to high frequency events.

Similar to Myth #1, the frequency of an incident alone is not a distinguishing feature, e.g. process safety related to higher frequency / lower consequence events. Lower consequence process safety events are actually a great way to learn and avoid catastrophes.

Lower consequence process safety events without harm, are often referred to as “near misses” and are valuable learning opportunities for organizations. They serve as early warning signs of potential systemic issues in the way health and safety is managed.

Here’s how low consequence events contribute to learning and avoiding catastrophes:

- Early Warning Signs: Lower consequence events act as early warning signs, indicating potential weaknesses in the system before they lead to major accidents.

- Identify Systemic Issues: Enable the identification of systemic issues that might not be apparent during routine checks and operations.

- Improve Safety Culture: Sharing the lessons learned from these events promotes a culture of transparency and continuous improvement.

- Enhance Risk Awareness: Analyzing these events enhances understanding of risks, leading to better predictability of material unwanted events.

- Refine Safety Protocols: The insights gained from these events can lead to the refinement of operational procedures and safety protocols.

- Prevent Escalations: Understanding the root causes of minor incidents can prevent the escalation of similar events into serious accidents or disasters 4.

By paying attention to and learning from lower consequence process safety events, organizations can significantly improve their overall safety performance and resilience against catastrophic failures.

This proactive approach is supported by safety experts and literature, emphasizing the importance of learning from every incident, regardless of its scale 5.

Myth #4: Personal and Process Safety is the absence of failures.

Many would argue the presence of effective controls is far more important than the absence of failures (Louvar, 2019). This underscores the proactive approach to effectively manage health and safety. It also moves away from using injury classification as a metric. Furthermore, it removes any reference to injury classification ais a risk consequence descriptors, e.g. moderate / major consequences should not be described as an LTI. Often an LTI is based on luck and does not truly describe the potential consequence.

Effective controls are mechanisms put in place to prevent incidents before they occur, rather than simply reacting to them after the fact.

Here’s a more detailed perspective on this concept:

- Proactive vs. Reactive: Effective controls are proactive measures that help to prevent accidents or failures from happening in the first place. They are designed to identify and mitigate risks, ensuring that potential issues are addressed before they lead to failures.

- Continuous Improvement: The implementation of effective controls is part of a continuous improvement process. It involves regular review and updating of safety measures to adapt to new risks and changing circumstances.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Investing in effective controls can be more cost-effective in the long run. While failures might not happen often, when they do, they can be costly in terms of both direct costs (repairs, fines, compensation) and indirect costs (reputation, downtime, loss of trust).

- Regulatory Compliance: Effective controls are often required to comply with safety regulations and standards. Their presence demonstrates an organization’s commitment to maintaining a safe work environment.

- Organizational Resilience: Organizations with effective controls are better equipped to handle unexpected events. This resilience can be a competitive advantage, as it allows the organization to maintain operations under various conditions.

“Any organization that seeks to assess how well it is managing process safety hazards cannot therefore rely on injury and fatality data; it must develop indicators that relate specifically to process hazards.” 6

Andrew Hopkins

In summary, the presence of effective controls is fundamental to a robust health and safety management. It emphasizes the importance of preventing incidents rather than just having a good track record of a few failures.

This proactive stance on health and safety is not only a best practice but also a strategic approach that can lead to long-term benefits for organizations.

Myth 5: Process safety is no more than following rules and regulations.

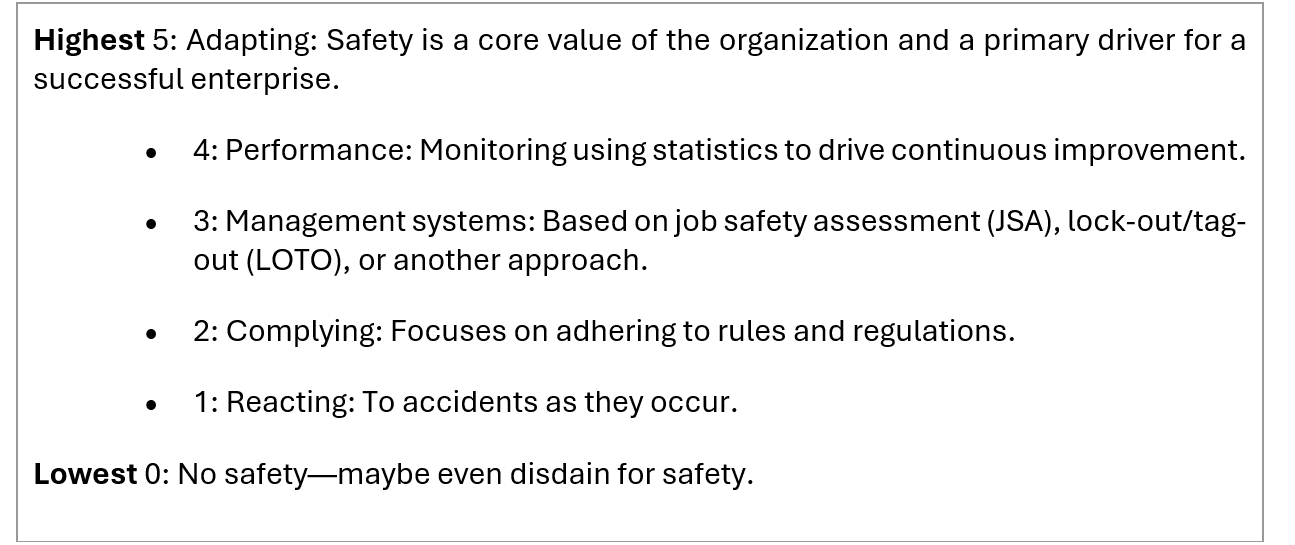

Myth 5 is falsified by Table 1-3, which shows the hierarchy of safety programs (Louvar, 2019).

The hierarchy ranges from level 0 (lowest level) to level 5 (highest level). The safety program must work its way through the levels from the bottom to the top: No levels can be skipped. Thus, level 5 includes all of the levels below it:

Level 5 is the highest level, at which the safety program is dynamic and adapting. Safety is a core value for everything that is done and the primary driving force for a successful enterprise.

Level 4 uses monitoring to obtain statistics on how well the safety program is performing. The performance monitoring identifies problems and corrects them. For instance, performance monitoring might indicate a large number of ladder incidents, which might be resolved by additional training in ladder safety.

Level 3 introduces management systems to assess hazards and provide procedures to manage hazards. A variety of management systems can be used to achieve this level, including job safety assessment (JSA), lock-out/tag-out (LOTO), management of change (MOC), and other means to control hazards during operations. Written management systems provide documentation to train operators and others and to ensure consistency in operating practices.

Level 2 is a safety program that consists of complying with rules and regulations. Rules and regulations can never be complete, however, and can never handle all situations. Regulations have legal authority and generally set a minimum standard for industrial operations.

Level 1 is a safety program that reacts to accidents as they occur. Accidents do result in changes, but only on a reactive basis, rather than the organization taking a proactive stance. Accidents continue to occur, although specific accidents are not likely to be repeated.

Level 0 consists of no safety program and maybe even disdain for safety. Such a program is destined to have continuous accidents, maybe even accidents that are repeated. No improvement is ever achieved.

The hierarchy of safety programs shown in Table 1-3 addresses Myth 5, since rules and regulations are only at level 2 (Louvar, 2019).

Conclusion

Regardless of your industry, it’s important to strike a balance between personal safety and process safety when managing critical control programs. Both aspects may vary in the level of importance based on unique risk profiles and risk appetite.

Understanding the organisation context, and identifying high energy hazards across both personal safety and process safety is crucial. This will help prioritise risks across critical assets, activities, processes and workplace environments.

Remember, safety is not just about avoiding failures; it’s about implementing effective controls and continuously learning from events and other early warning signs.

References:

- American Petroleum Institute API RP 754, Process Safety Performance Indicators for the Refining and Petrochemical Industries 3rd Edition August 2021 ↩︎

- Louvar, D. A. (2019). Chemical Process Safety: Fundamentals with Applications, 4th Edition. In J. F. Daniel A. Crowl, Chemical Process Safety: Fundamentals with Applications, 4th Edition. Pearson. ↩︎

- ICMM, I. C. (2015). Critical Control Management Implementation Guide ↩︎

- Azizi, W. (2016). Predict Incidents with Process Safety Performance Indicators. American Institute of Chemical Engineers. ↩︎

- Engineers, A. I. (2017). Process Safety Visions: Enhanced Application and Sharing of Lessons Learned ↩︎

- Hopkins, A. (2007). Thinking About Process Safety Indicators. Regulatory Institutions Network (RegNet) ↩︎